毛竹TIP基因成员鉴定及其响应胁迫的表达分析

编号

lyqk008766

中文标题

毛竹TIP基因成员鉴定及其响应胁迫的表达分析

作者单位

国际竹藤中心竹藤资源基因科学与基因产业化研究所 国家林业和草原局/北京市共建竹藤科学与技术重点实验室 北京 100102

期刊名称

世界竹藤通讯

年份

2021

卷号

19

期号

1

栏目名称

学术园地

中文摘要

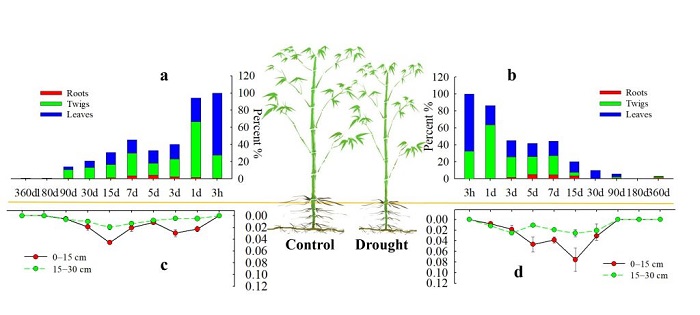

液泡膜内在水通道蛋白(TIPs)在调节植物细胞膨压适应逆境胁迫环境过程中发挥着重要作用。研究毛竹TIP基因成员的分子特征及其在不同逆境胁迫条件下的表达模式,对揭示其在毛竹应答胁迫中的功能具有重要意义。利用生物信息学方法在毛竹基因组中共鉴定19个编码完整TIP蛋白的基因(PeTIP1-1~PeTIP1-3、PeTIP2-1~PeTIP2-4、PeTIP3-1~PeTIP3-2、PeTIP4-1~PeTIP4-7和PeTIP5-1~PeTIP5-3);PeTIPs编码氨基酸的长度为238~434 aa,相对分子量为25.06~44.03 kDa;亚细胞位置预测显示,所有PeTIPs均定位于液泡膜上。PeTIPs包含7个保守基序,其中有4个为共有基序,不同成员的Ar/R选择性过滤器具有一定的差异,而Froger's残基均较为保守。系统进化分析显示,来自毛竹、水稻等6个物种的71条TIP氨基酸序列可分为5个分支,各分支中PeTIPs成员依次为3、4、2、7和3个。共线性分析结果表明,PeTIPs成员间共存在10对片段重复,在12个PeTIPs与水稻8个TIP基因间发现18对片段重复,这些重复基因多半发生在PeTIP4s和PeTIP5s中,且基因对的非同义对同义取代比(Ka/Ks)均小于1.0,表明PeTIPs经复制后的功能差异不大。在PeTIPs启动子区域中,发现多种与胁迫、激素响应相关的调控元件。基于叶片RNA-seq数据分析表明,不同PeTIPs响应低温、干旱和强光胁迫的表达模式均存在一定差异,既有显著性变化的成员(如PeTIP1-1和PeTIP1-2),也有几乎无变化的成员(如PeTIP5的成员)。qPCR结果显示,在不同胁迫条件下毛竹叶片和根中的PeTIPs的表达模式不同,多数呈现不同程度的显著上调,亦有在某一处理下基因表达变化不明显(如强光下叶片中的PeTIP1-1、PeTIP1-3和PeTIP4-2;干旱下根中的PeTIP1-1和PeTIP1-2),个别基因呈现下调(如低温下叶片中的PeTIP1-1)。毛竹叶片和根中PeTIPs的表达变化模式差异,说明它们在响应不同环境胁迫中可能发挥着不同的作用。

关键词

毛竹

液泡膜内在水通道蛋白

分子特征

逆境胁迫

基因表达

基金项目

国家自然科学基金(31971736);国际竹藤中心基本科研业务费专项资金项目(1632018005)。

英文标题

Identification of TIP Genes and Their Expression Patterns under Stresses in Moso Bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis)

作者英文名

Zhu Chenglei, Yang Kebin, Gao Zhimin

单位英文名

Institute of Gene Science and Industrialization for Bamboo and Rattan Resources, International Center for Bamboo and Rattan, Key Laboratory of National Forestry and Grassland Administration/Beijing for Bamboo & Rattan Science and Technology, Beijing 100102, China

英文摘要

Tonoplast intrinsic aquaporin proteins(TIPs) play a significant role in regulating cell turgor pressure to adapt to adversity stresses. Studying the molecular characteristics of TIP gene members of moso bamboo (Phllostachys edulis) and their expression patterns under different stress conditions is of great significance to reveal their functions in response to stresses. Bioinformatics methods were used to systematically identify the gene members of TIP family in moso bamboo genome, and a total of 19 genes encoding complete TIP proteins were obtained (PeTIP1-1~PeTIP1-3, PeTIP2-1~PeTIP2-4, PeTIP3-1~PeTIP3-2, PeTIP4-1~PeTIP4-7 and PeTIP5-1~PeTIP5-3). The length of the amino acids encoded by PeTIPs ranged from 238 to 434 aa, and the relative molecular weights were 25.06~44.03 kDa. Subcellular location prediction showed that all PeTIPs were located on the tonoplast. PeTIPs contained 7 conserved motifs, 4 of which were shared motifs. The Ar/R selective filters of different PeTIPs had certain differences, while Froger's residues were relatively conservative. Phylogenetic analysis showed that 71 TIP amino acid sequences from 6 species such as moso bamboo and rice can be divided into 5 branches, and the members of PeTIPs in each branch are 3, 4, 2, 7 and 3 in turn. The results of collinearity analysis showed that there were 10 pairs of fragment duplications among members of PeTIPs, and 18 pairs of fragment duplications were found between 12 PeTIPs and 8 TIP genes in rice. Most of these duplication genes occurred in PeTIP4s and PeTIP5s, and the nonsynonymous and synonymous substitution ratios (Ka/Ks) were all less than 1.0, indicating that PeTIPs had little functional difference after replication. A variety of regulatory elements related to stress and hormone responses were found in the promoters of PeTIPs. Analysis based on leaf RNA-seq data showed that the expression patterns of different PeTIPs in response to low temperature, drought and strong light stress were different. There are not only members with significant changes (such as PeTIP1-1 and PeTIP1-2), but also members with almost no changes (As a member of PeTIP5). The qPCR results showed that the expression patterns of PeTIPs in the leaves and roots of moso bamboo were different under different stress conditions, and most of them showed significant up-regulation to varying degrees. There were also gene expression changes that were not obvious under a certain treatment (such as PeTIP1-1, PeTIP1-3 and PeTIP4-2 in leaves under high light, PeTIP1-1 and PeTIP1-2 in roots under drought), and individual genes were down-regulated (e.g. PeTIP1-1 in leaves under low temperature). The different expression patterns of PeTIPs in leaves and roots indicate that they may play different roles in response to different environmental stresses.

英文关键词

Phyllostachys edulis;tonoplast intrinsic aquaporin protein;molecular characteristics;adversity stress;gene expression

起始页码

1

截止页码

11

作者简介

朱成磊,博士研究生,研究方向为毛竹生长发育的分子基础。E-mail:zhuchenglei@icbr.ac.cn。

通讯作者介绍

高志民,研究员,博士,从事竹藤生长发育的分子基础研究。E-mail:gaozhimin@icbr.ac.cn。

E-mail

gaozhimin@icbr.ac.cn

DOI

10.12168/sjzttx.2021.01.001

参考文献

[1] FORTIN M G, MORRISON N A, VERMA D P. Nodulin-26, aperibacteroid membrane nodulin is expressed independently of the development of the peribacteroid compartment[J]. Nucleic Acids Research, 1987, 15(2): 813-824.

[2] MAUREL C, REIZER J, SCHROEDER J I,et al. The vacuolar membrane protein gamma-TIP creates water specific channels in Xenopus oocytes[J]. The EMBO Journal, 1993, 12(6): 2241-2247.

[3] AHMED. Evolutionary and predictive functional insights into the aquaporin gene family in theallotetraploid plant Nicotiana tabacum[J]. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2020, 21(13): 4743. doi:10.3390/ijms21134743

[4] GOMES D, AGASSE A, THIEBAUD P, et al. Aquaporins are multifunctional water and solute transporters highly divergent in livingorganisms[J]. Elsevier Biochimica et Biophysica Acta(BBA)-Biomembranes, 2009, 1788(6): 1213-1228.

[5] MAUREL C, TACNET F, GUCLU J, et al. Purified vesicles of tobacco cell vacuolar and plasma membranes exhibit dramatically different water permeability and water channel activity[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 1997, 94(13): 7103-7108.

[6] GERBEAU P, GVCLV J, RIPOCHE P, et al. Aquaporin Nt-TIPa can account for the high permeability of tobacco cell vacuolar membrane to small neutral solutes[J]. The Plant Journal, 1999, 18(6): 577-587.

[7] MAESHIMA M. Tonoplast transporters: organization and function[J]. Annual Review of Plant Physiology and Plant Molecular Biology, 2001, 52: 469-497.

[8] LOQUÉ D, LUDEWIG U, YUAN L, et al. Tonoplast intrinsic proteins ATTIP2;1 and ATTIP2;3 facilitate NH3 transport into the vacuole[J]. Plant Physiology, 2005, 137(2): 671-680.

[9] DYNOWSKI M, MAYER M, MORAN O, et al. Molecular determinants of ammonia and urea conductance in plant aquaporinhomologs[J]. FEBS Letters, 2008, 582(16): 2458-2462.

[10] PANG Y Q, LI L J, REN F, et al. Overexpression of the tonoplast aquaporin AtTIP5;1 conferred tolerance to boron toxicity in Arabidopsis[J]. Journal of Genetics and Genomics, 2010, 37(6): 389-397.

[11] HE Z Y, YAN H L, CHEN Y S, et al. An aquaporin PvTIP4;1 from Pteris vittata may mediate arsenite uptake[J]. New Phytology, 2016, 209(2): 746-761.

[12] BALASAHEB KARLE S, KUMAR K, SRIVASTAVA S, et al. Cloning, in silico characterization and expression analysis of TIP subfamily from rice(Oryza sativa L.)[J]. Gene, 2020, 761: 145043. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2020.145043.

[13] PENG Y, LIN W, CAI W, et al. Overexpression of a Panax ginseng tonoplast aquaporin alters salt tolerance, drought tolerance and cold acclimation ability in transgenic Arabidopsis plants[J]. Planta, 2007, 226(3): 729-740.

[14] BEZERRA-NETO J P, DE ARAÚJOA F C, FERREIRA-NETO J R C, et al. Plant aquaporins: diversity, evolution and biotechnological applications[J]. Current Protein and Peptide Science, 2019., 20(4): 368-395.

[15] REGON P, PANDA P, KSHETRIMAYUM E, et al. Genome-wide comparative analysis of tonoplast intrinsic protein(TIP) genes in plants[J]. Functional & Integrative Genomics, 2014, 14(4): 617-629.

[16] PENG Z H, LU Y, LI L B, et al. The draft genome of the fast-growing non-timber forest species moso bamboo (Phyllostachys heterocycla)[J]. Nature Genetics, 2013, 45(4): 456-461.

[17] SUN H Y, WANG S N, LOU Y F, et al. Whole-genome and expression analyses of bamboo aquaporin genes reveal their functions involved in maintaining diurnal water balance in bamboo shoots[J]. Cells, 2018, 7(11): 195. doi: 10.3390/cells7110195.

[18] 孙化雨, 娄永峰, 李利超, 等. 毛竹TIPs全基因组分析及表达模式研究[J]. 林业科学研究, 2016, 29(4): 521-528.

[19] ZHAO H S, GAO Z M, WANG L, et al. Chromosome-level reference genome and alternative splicing atlas of moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis)[J]. GigaScience, 2018, 7(10): giy115. doi: 10.1093/gigascience/giy115.

[20] HUANG Z, JIN S H, GUO H D, et al. Genome-wide identification and characterization of TIFY family genes in moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis) and expression profiling analysis under dehydration and cold stresses[J]. PeerJ, 2016, 27(4): e2620. doi: 10.7717/peerj.2620.

[21] ZHAO H S, LOU Y F, SUN H Y, et al. Transcriptome and comparative gene expression analysis of Phyllostachys edulis in response to high light[J]. BMC Plant Biology, 2016, 28(16): 34. doi: 10.1186/s12870-016-0720-9.

[22] LESCOT M, DÉHAIS P, THIJS G, et al.PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences[J]. Nucleic Acids Research, 2002, 30(1): 325-327.

[23] CHEN C J, CHEN H, HE Y H, et al. TBtools: an integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data[J]. Molecular Plant, 2020, 13(8): 1194-1202.

[24] ZHANG M, LIU Y, SHI H, et al. Evolutionary and expression analyses of soybean basic leucine zipper transcription factor family[J]. BMC Genomics, 2018, 19(1): 159. doi: 10.1186/s12864-018-4511-6.

[25] WANG Y P, TANG H B, DEBARRY J D, et al. MCScanX: a toolkit for detection and evolutionary analysis of gene synteny and collinearity[J]. Nucleic Acids Research, 2012, 40(7): e49. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1293.

[26] JONES D T, TAYLOR W R, THORNTON J M. The rapid generation of mutation data matrices from protein sequences[J]. Bioinformatics, 1992, 8(3): 275-282.

[27] KUMAR S, STECHER G, TAMURA K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets[J]. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 2016, 33(7): 1870-1874.

[28] FAN C J, MA J M, GUO Q R,et al. Selection of reference genes for quantitative real-time PCR in bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis)[J]. PLoS One, 2013, 8(2): e56573. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056573.

[29] LIVAK K J, SCHMITTGEN T D.Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-△△CT method[J]. Methods, 2001, 25(4): 402-408.

[30] JOHANSON U, KARLSSON M, JOHANSSON I, et al. The complete set of genes encoding major intrinsic proteins in Arabidopsis provides a framework for a new nomenclature for major intrinsic proteins in plants[J]. Plant Physiology, 2001, 126(4): 1358-1369.

[31] CHAUMONT F, BARRIEU F, WOJCIK E, et al. Aquaporins constitute a large and highly divergent protein family in maize[J]. Plant Physiology, 2001, 125(3): 1206-1215.

[32] ZARDOYA R. Phylogeny and evolution of the major intrinsic protein family[J]. Biology of the Cell, 2005, 97(6): 397-414.

[33] FORREST K L, BHAVE M. Major intrinsic proteins(MIPs) in plants: a complex gene family with major impacts on plant phenotype[J]. Functional & Integrative Genomics, 2007, 7(4): 263-289.

[34] WALLACE I S, ROBERTS D M. Homology modeling of representative subfamilies of Arabidopsis major intrinsic proteins. Classification based on the aromatic /arginine selectivity filter[J]. Plant Physiology, 2004, 135(2): 1059-1068.

[35] MAUREL C, VERDOUCQ L, LUU D T, et al. Plant aquaporins: Membrane channels with multiple integrated functions[J]. Annual Review of Plant Biology, 2008, 59(1): 595-624.

[36] HOVE R M, BHAVE M. Plant aquaporins with non-aqua functions: deciphering the signature sequences[J]. Plant Molecular Biology, 2011, 75(4-5): 413-430.

[37] HUSBAND B, SCHEMSKE D W. Cytotype distribution at a diploid-tetraploid contact zone in Chamerion (Epilobium) angustifolium (Onagraceae)[J]. American Journal of Botany, 1998, 85(12): 1688-1694.

[38] KALDENHOFF R, FISCHER M. Functional aquaporin diversity inplants[J]. Elsevier Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes, 2006, 1758(8): 1134-1141.

[39] WANG LL, CHEN A P, ZHONG N Q, et al. The Thellungiella salsuginea tonoplast aquaporin TsTIP1;2 functions in protection against multiple abiotic stresses[J]. Plant Cell Physiology, 2014, 55(1): 148-161.

[40] ANISIMOVA M, BIELAWSKI J P, YANG Z. Accuracy and power of the likelihood ratio test in detecting adaptive molecular evolution[J]. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 2001, 18(8): 1585-1592.

[41] ROTH C, LIBERLES D A. A systematic search for positive selection in higher plants(Embryophytes)[J]. BMC Plant Biology, 2006, 6: 12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-6-12.

[42] HERNANDEZ-GARCIA C M AND FINER J J. Identification and validation of promoters and cis-acting regulatory elements[J]. Plant Science, 2014, 217-218: 109-119.

[43] XU Z, WANG M, GUO Z, et al. Identification of a 119-bp Promoter of the maize sulfite oxidase gene(ZmSO) that confers high-level gene expression and ABA or drought inducibility in transgenic plants[J]. International Journal of Molecular Science. 2019, 20(13): 3326. doi: 10.3390/ijms20133326.

[44] MAJDA M, ROBERT S. The role of auxin in cell wall expansion[J]. International Journal Molecular Sciences, 2018, 19(4): 951. doi: 10.3390/ijms19040951.

PDF全文

浏览全文

-

相关记录

更多

- 振兴遂昌竹产业经济的发展战略 2022

- 毛竹林大小年形成机制及调控措施研究进展 2021

- 木本植物树皮研究进展 2021

- “六力”驱动破解湖南毛竹下山难题 2024

- 毛竹良种‘元宝竹’ 2023

- 江苏省宜兴市毛竹资源利用历史变迁及现状 2023

打印

打印